Why (nearly) All Blocks in Barcelona Look the Same

History and Features of the Barcelona Grid Explained

Let us begin with a small, fun exercise. Open Maps application, search "Barcelona", and zoom in a little bit. You will see a pattern of square blocks repeated through the city. The blocks are so precise; they almost resemble a pattern embossed on clothing fabric.

So how did Barcelona end up with such a design? What were the reasons and objectives behind it? How this layout has evolved over the years? And what are the pros and cons of a grid plan? Read on to learn more on the story of Barcelona’s grid plan.

Introduction

Barcelona, as we can see on the map, is located on the northeast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia. Home to over 1.5 million citizens and several UNESCO World Heritage sites, Barcelona is a major tourist destination.

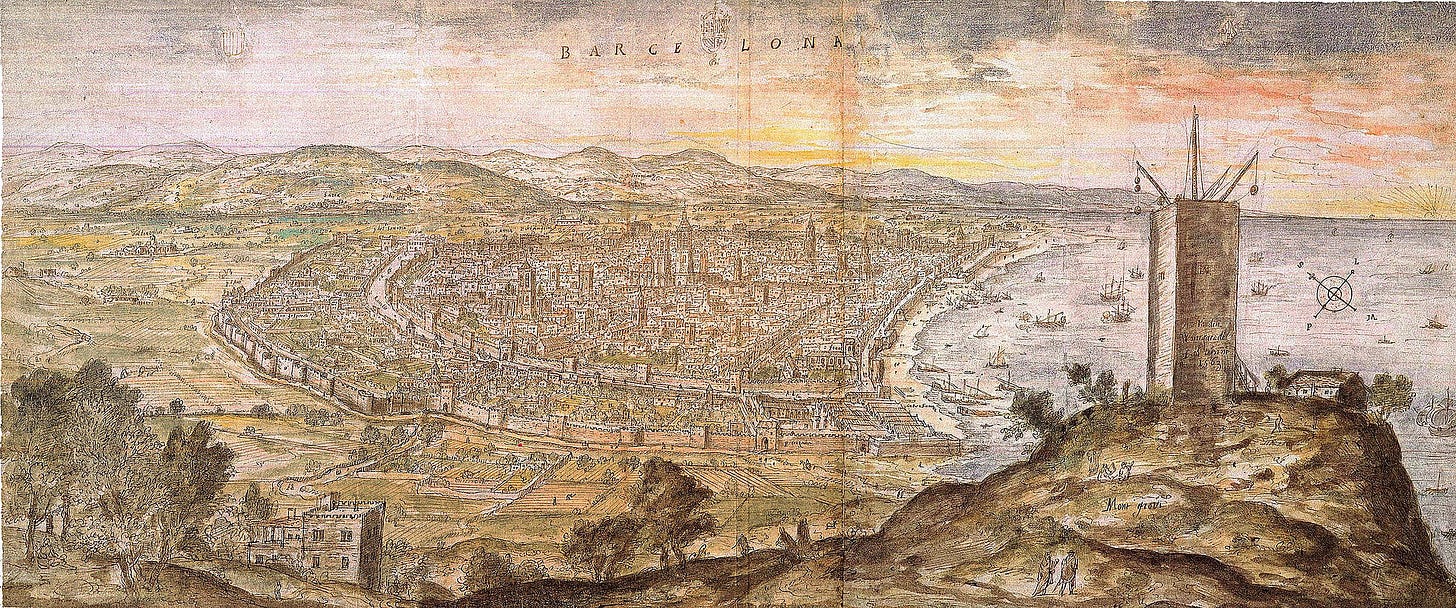

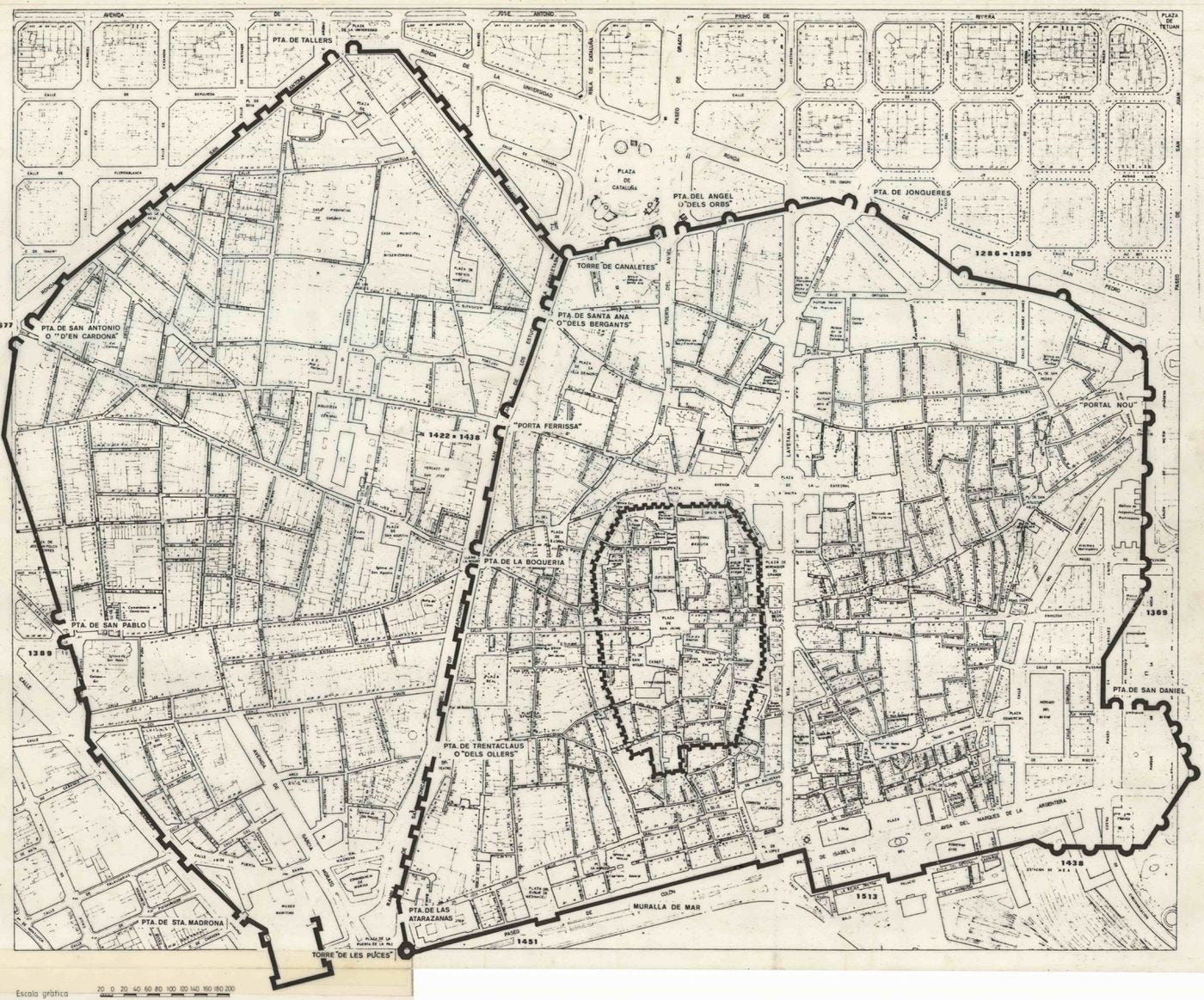

Like many old cities, Barcelona was once confined by its ancient walls. Its streets were initially arranged randomly to connect residences. However, as a result of massive economic boom in the nineteenth century, the population expanded rapidly. This burgeoning population strained the walled city's limited space and resources, and caused overcrowding and unhygienic living conditions.

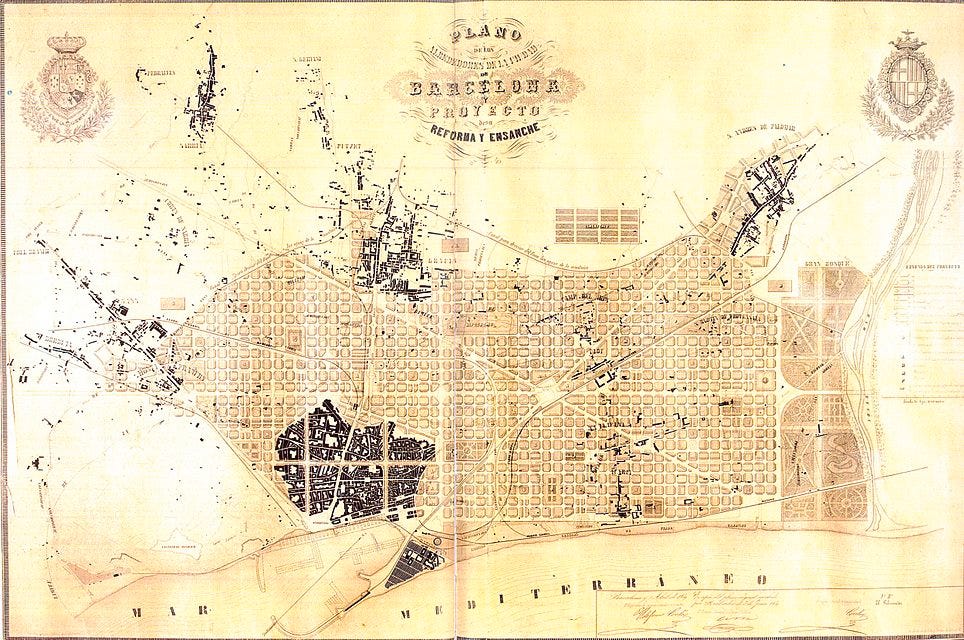

To counter this situation, the city had to expand beyond its ancient walls. As a result, an expansion of Barcelona was planned along the adjoining plain. Ildefons Cerdà, a Catalan Engineer, came up with the masterplan, which proposed to expand Barcelona from the old walled city and include the surrounding villages such as Gràcia and Sarrià.

Ildefons Cerdà- The Mind Behind the Barcelona Grid

The development of Barcelona's expansion ("Eixample" in Catalan) is credited to Ildefons Cerdà i Sunyer, a Spanish Civil Engineer. He also coined the new word and discipline “urbanization”. Due to his extensive research and practical work on the subject, Cerdà is widely regarded as the founder of modern town planning and his design is regarded as progressive even by today’s standards.

In his preparation for designing Barcelona's extension, Cerdà failed to find suitable research work on city design. Hence, he himself undertook the task of writing a design code to build a highly efficient city. He developed many skills in the process, including surveying, mapmaking, and public health analysis. In these relentless efforts, he eventually lost all his family's inheritance and died in 1876 heavily indebted, and without having received compensation for his chief masterpiece, the Eixample.

In order to design Barcelona's extension, Cerdà set out to study the conditions of its residents, and was disappointed with the state of the working class. His plan envisioned an expansion that would not face the problems of congestion and health epidemics like the old city, and would be a model of efficient, safe and hygienic urban living.

Cerdà's plan was based on egalitarianism (the doctrine of all people being equal and deserving equal rights and opportunities). He proposed to build the Eixample in the form of a grid of equally sized square blocks (called manzanas), which were to be divided by wide streets for easy navigation. Cerdà wanted to ensure all citizens got equal and sufficient access to water, sunlight, ventilation, greenery, sanitation, and transportation.

In the plan, buildings were to be regular in height and spacing, and green spaces were to come about in the middle of each block. The ground floor of the buildings was allocated for commercial outlets, the first floor for middle class (who previously used to live on the sidelines of town), and artisans were to live on the upper stories. This way, all classes of the public would share the same spaces and hygienic conditions, thus countering social disparity.

Eixample- The Extension of Barcelona

Barcelona's Eixample (Catalan for "extension") project of the 1850s is widely considered one of the best city plans in the world. Cerdà's vision was to combine the benefits of rural living, such as lush green spaces, with the commercial nature of urban areas. The plan divided land into square blocks of equal size (exactly 113.3 by 113.3 meters), with green spaces at the center of each block.

The size of the blocks was kept large to enable the creation of large open spaces and to allow adequate sunlight and ventilation for the perimeter buildings. The blocks are oriented NW-SE to allow adequate sunshine throughout the day. Groups of multiple blocks were to serve as self-contained neighbourhoods, with hospitals, parks, and plazas spread evenly throughout the city to maximize equity.

The regular grid design was chosen for its ease of navigation. Roads were planned to be 20 m and 50 m wide respectively for collector and arterial roads to allow for smooth flow of traffic. The blocks have corners chamfered at 45 degrees to allow for greater visibility and easy turning of trams. As per the original plan, each of the blocks were to have buildings on just two sides, covering under 50 percent of the total area, with much of the area being dedicated for green space. The buildings were to be restricted to a height of 20 m to allow for the passage of sunlight.

While the Eixample project is highly appreciated in urban planning even today, Cerdà's plan was met with criticism from some architects at the time for uniformity of the blocks. It was argued that the constant form of the blocks would leave no room for architectural structures such as monuments. Eventually, Cerdà's original design was subjected to a number of modifications. The buildings went up higher than the prescribed limits, and the blocks ended up being enclosed by buildings on all four sides, instead of two. The space occupied by buildings, thus, grew from the planned 67,000 square meters to about 300,000 square meters in the 1950's, and has been only increasing ever since. The streets were laid narrower than planned and most of the inner space is now occupied by car parks and shopping centers. Culturally too, Cerdà's vision of countering social disparity remained unfulfilled, as the inhabitants of the Eixample are mostly higher class rather than of mixed composition.

More on the Grid Plan

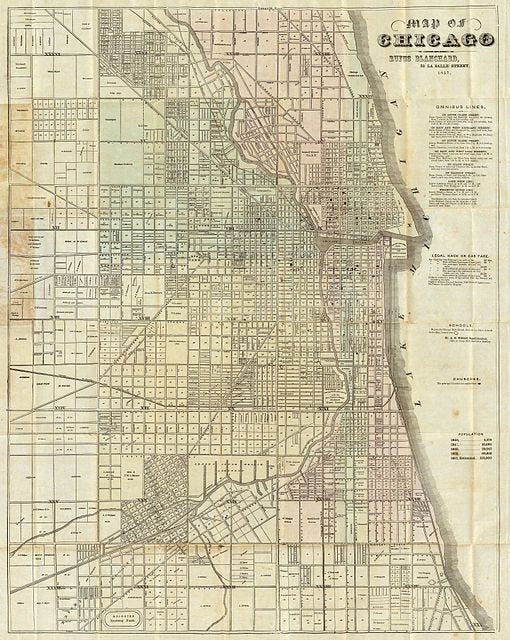

Like Barcelona, many other cities of the world were built with a grid layout, for instance New York, Chandigarh and Dubai. In the grid plan, all streets are placed at right angles to each other, forming an orthogonal network of roads. While the grid layout was used extensively in the planning of several cities in the 19th and early 20th centuries, it actually dates back to ancient times and has been found in archaeological surveys of multiple cultures, including the earliest planned cities of the world such as Mohenjo-daro.

The obvious advantage of grid plan is that it makes navigation easy for both vehicles and pedestrians, as straight lines result in simpler and oftentimes the shortest routes to navigate. Another benefit is that a grid layout divides a city into blocks of regular shape and size, which eases the process of trading and developing land, and also minimizes wastage of space. The grid design also offers the advantage of flexibility. With time, as social conditions change, buildings can be modified, renovated or replaced easily.

However, the grid plan has downsides too, such as the greater number of intersections necessitated, which create hindrance to smooth flow of motor traffic. Higher number of intersections also means more crossing points for pedestrians, and greater risk of traffic collisions and injures. Also, most cities with grid layout have equal road widths throughout, irrespective of the road type. This neglect of road hierarchy results in inefficiency in traffic movement as such plan does not differentiate between the main arterial roads and smaller, neighbourhood streets. Examples can be cited of both positive and negative outcomes of the grid layout. The success of a grid plan depends on several factors such as shape and size of blocks, width of pavement, traffic characteristics, and so on.

Superblocks- A Creative Solution to Counter Traffic

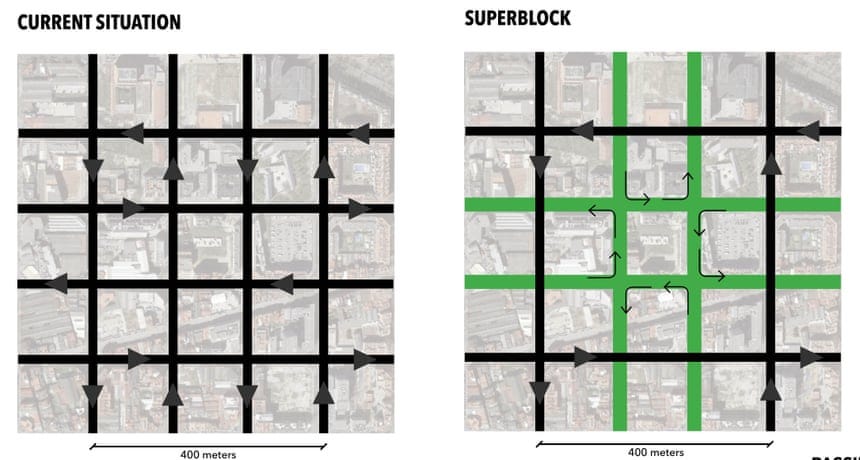

Despite its strengths, Cerdà's plan did not foresee the dependency on automobile for transit and the associated traffic and pollution woes. Massive surge in the number of personal vehicles over the decades has led to dangerous levels of pollution and noise, in addition to traffic congestion. To counter these adverse effects, the idea of superblocks ("super-illes" in Catalan) consisting of nine city blocks is being implemented in Barcelona. The aim is to make internal streets safer for pedestrians and encourage walking, and give space for sports and cultural activities.

A superblock is a large area comprising a number of city blocks, bounded by arterial roads, designed to alleviate traffic from inner roads and make streets safer for pedestrians. A superblock forms a grid of main arterial roads, and contains a network of narrower interior streets within this grid. Superblocks can be implemented on existing city layouts by modifying traffic rules, such as by introducing new signals, altering speed limits, and prohibiting through traffic on the inner roads. Only traffic serving local needs is allowed on the interior roads. Vehicles entering a superblock are allowed access to local businesses or their residences, but at speeds as low as 10 kmph, and are not allowed to exit to the arterial road on the opposite side through an inner road.

The idea of superblocks originated when the public bus network of Barcelona was modified such that the number of routes was minimized by allowing buses to navigate only along arterial roads, and frequency of service increased. As many streets were freed from movement of buses due to this initiative, the idea was eventually expanded to cover other vehicles as well to help curb air pollution and traffic problems, and create space for outdoor activities in the city.

With the strategy of superblocks, Barcelona aims to reduce car usage by 20% and encourage use of other modes, such as walking and public transit. As a result, air and noise pollution is estimated to reduce significantly. By limiting space for motor transport by 60%, pedestrians can enjoy privilege on about 90% of space on the inner streets, and about 300 km of new cycling lanes can be introduced. The idea of superblocks, however, has been criticised from some city residents who have complained of increased distance for previously short trips, and the increased traffic on the arterial roads.

List of References

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barcelona

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Architecture_of_Barcelona

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ildefons_Cerd%C3%A0

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grid_plan

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/City_block#Superblock

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/may/17/superblocks-rescue-barcelona-spain-plan-give-streets-back-residents

https://citiesofthefuture.eu/superblocks-barcelona-answer-to-car-centric-city/

https://theculturetrip.com/europe/spain/articles/why-is-barcelona-built-in-squares/?amp=1

https://theculturetrip.com/europe/spain/articles/7-curious-facts-you-need-to-know-about-barcelona/?utm_source=amp_page

https://amp.theguardian.com/cities/2016/apr/01/story-cities-13-eixample-barcelona-ildefons-cerda-planner-urbanisation

https://www.vox.com/platform/amp/energy-and-environment/2019/4/8/18266760/barcelona-spain-urban-planning-history

https://www.amusingplanet.com/2013/07/the-peculiar-architecture-and-design-of.html?m=1